The Place Between Sleeping and Waking

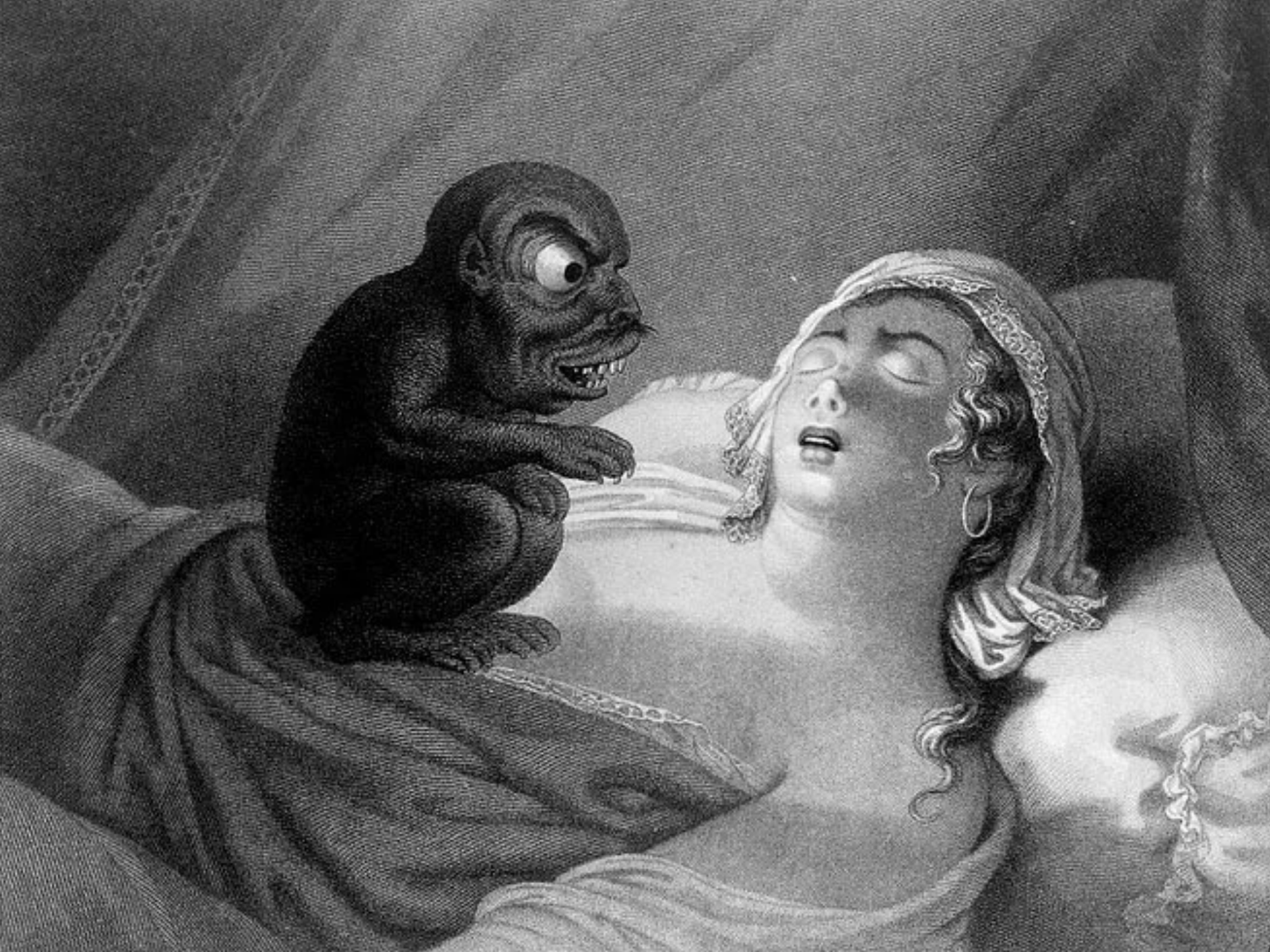

An illustration of sleep paralysis, by Steve Teare

You won’t believe the things I’ve seen/felt/heard

As a child, I always wanted to believe in ghosts. I felt my surname gave me a right to some ghost friends (and I always assumed they’d be friendly) and I tried hard to find them, to no avail. Even though I was a sensitive, anxious child with a trademark “over-active imagination”, ghostly experiences eluded me.

That is, until my late twenties.

It was morning and I was in bed and ill enough with a fever to be off work. From downstairs, I heard my sister call my nickname, clear as a bell. That’s strange, I thought. My sister was over two hundred miles away. I was amused and excited, because I knew this auditory apparition was no ghost. It was my first hallucination. My brain had finally invented something that felt utterly real.

Cute enough to model a soft toy after. Stipple engraving by J.P. Simon, 1810.

Sleep Paralysis and Hallucinations

Prior to this, I’d suffered from sleep paralysis, but I mostly forgot about it once I’d woken properly. Sleep paralysis occupies an uncomfortable space where waking and sleep overlap: your body is almost completely paralysed (it’s called atonia, a safety precaution to stop us acting out our dreams), but your mind seems to be very awake, though it isn’t completely. You’ve glitched.

The scientific name is hypnagogia: the transitional stage between wakefulness and sleep. Some people try to get into this space for the purposes of lucid dreaming. Others fervently wish to avoid it, because it belongs to sleep paralysis and strange and sometimes terrifying visions - hypnagogic hallucinations.

For me, sleep paralysis would mainly occur on days when I would wake up to my alarm, but not be in any hurry to get up. I’d turn onto my back and fall asleep again. Then I’d find myself awake but unable to breathe, move, or open my eyes. My throat was always restricted and I’d be scared, desperately willing myself to wake up, but utterly powerless to do anything. I don’t know how the episodes ended. I certainly never woke up immediately from the paralysis, so I must have fallen fully asleep again.

Usually, that’s all there was to it, but occasionally, hallucinations have accompanied them. I can’t be sure, though: I’ve never been aware of the paralysis at the same time. Regardless, both the paralysis and hallucinations exist in that hypnagogic state.

Sometimes, the hallucination will be as simple as a bang that I hear very clearly, close to my head. The physical sensations are more interesting, though. On one occasion, I felt the weight on the mattress as someone who wasn’t there sat on the other side of the bed, the duvet tightening over my neck. Another time, I heard someone pull out drawers aggressively and close them again, just across from me: I felt the vibrations. Most recently, last week, I felt an arm reach round me and a hand rest on my shoulder - a ghostly embrace, since I was lying on my back. I thought to myself, ‘I should probably be scared by this,’ chuckled, and rolled onto my side.

I’ve only had one visual hallucination. I was on my back and saw an indistinct shape hovering about four feet up in the air above the bottom of my bed. I squinted at it, trying to decipher the object. A tiny UFO, perhaps. No — it was a vision of my hairdryer. Why must my hallucinations be so mundane?

An illustration by R. Fresson

Terrors in the night

I’ve asked other people about their experiences, and they have far more dramatic stories to tell. One person told me of a recurring hallucination he had of being suddenly awoken by a ghostly hand trying to drag him out of bed by gripping his leg, which sounds terrifying. Of course, he wasn’t actually awake. Another person believed for years that they were being abducted by aliens due to hallucinations that began in childhood. And quite a lot of people told me that they had a real sense of a malign presence in their room, sometimes accompanied by a ghostly figure in a corner, or by sinister whispers.

Like me, others get less macabre hallucinations: the sensation of a cat walking on them, when they don’t have a cat; or simply the feeling of floating.

What I find especially interesting about all these very personal and affecting experiences is that they are so universal that they can be categorised. The Sleep Foundation reports that there are three types of hallucinations:

Intruder hallucinations, when the presence of a unknown person or thing is felt;

Chest pressure hallucinations, which can make the sleeper feel they’re suffocating. They can accompany intruder hallucinations;

Vestibular-motor (V-M) hallucinations, which describe sensations of movement, like flying, floating, or other ‘out of body’ sensations.

While lots of the experiences mentioned above fall into one or more of these categories, weirdly, none of them has room for the auditory or visual hallucinations that a lot of people experience. It does seem that it’s the pressure sensation that is felt most commonly, and which is also the feature of sleep paralysis that links humans across the world and right through history.

Henry Fuseli’s 1781 painting The Nightmare is one of the most famous representations of the demon-on-the-chest experience of sleep paralysis. Unsurprisingly, there are few paintings of men in their nightwear being visited in their night, whilst the images of forlorn, sleeping women get more and more nude and more and more erotic through the ages.

The History of Nightmares

When Samuel Johnson wrote A Dictionary of the English Language of 1755, he defined a nightmare as ‘A morbid oppression in the night, resembling the pressure of weight upon the breast.’ It’s an interesting definition, showing that it’s only relatively recently that the term has changed to indicate unpleasant or frightening dreams: previously, the hallucinatory aspect was the nightmare.

By the way, the ‘mare’ part of the word has nothing at all to do with a female horse. It has its roots in the ‘heathen mythology’ (as Johnson puts it) of the Old English ‘mare’, a malicious demon or goblin that rides on people’s chests while they sleep, causing bad dreams. This tormenting mare can be traced back to 13th Century Scandinavia folklore, to 14th Century German texts, as well as to various Slavic mythologies.

In fact, every culture seems to have a mythology attached to not just bad dreams, but the specific sensation of something pressing down on one’s chest during the night. There are far too many to go into here (just scroll down the Wikipedia page for ‘night hag’ to get an idea, or for more juicy details), but to give you the idea . . .

In Pakistani mythology, sleep paralysis is considered to be an encounter with Shaitan (evil demons) who take over your body, probably due to black magic performed by jealous enemies.

In Fiji, the experience is interpreted as kana tevoro, being "eaten" by a demon.

In Catalonia, the Pesanta is an enormous dog (sometimes a cat) that goes into a sleeper’s house in the night and lies on their chest, making it difficult for them to breathe and causing them the most horrible nightmares. It is described as black and hairy and with steel paws, but full of holes so that it can't take anything.

In Brazil, the mythological pisadeira ("she who steps") is a tall, skinny old woman, with white tangled hair, staring red eyes, and an evil laugh. She lives on rooftops, waiting to step on the chest of those who sleep with a full stomach.

In Ethiopian culture the word dukak ("depression") is used, an evil spirit that possesses people during their sleep. It’s thought to be a symptom of withdrawal from the stimulant khat.

Some of the folklore suggests possible reasons for sleep paralysis which tie in with current scientific ideas: sleeping on your back, eating too close to bedtime, consumption of toxins, withdrawal from toxins, and low mood.

The Nightmare, an engraving by Thomas Holloway from 1791, based on Fuseli’s painting (above). As we’ve established, nightmares have nothing to do with horses, but one’s been thrown in here for good measure.

Lust, Sin and Demons

Other myths continually point to the presence of some kind of incubus or succubus. In mythology, an incubus is a demon in male form that lies upon the body of a sleeping person in an attempt to seduce them. A succubus is a demon in female form. Mentions of these creatures and their lascivious intentions go back to 2400 BC, and you can well imagine the concerns that religious men had with the phenomenon throughout history. So terrified were they of erotic dreams that they thought it necessary to preach against ‘demoniality’ (intercourse between a person and a demon), warning that such sinful activity would weaken one’s physical or mental health, and even lead to death.

The myths of incubi and succubi are amusing in that respect, with various religious leaders waging a pointless battle against erotic dreams and subconscious desire. But the mixture of the sexual with the unpleasant weight and pressure of sleep paralysis makes for a strange concoction, and even a very troubling one in the case of some women, since it was believed that pregnancies could result from incubi. King James (who was obsessed with the supernatural) even thought up two explanations for how an incubus could achieve this in his 1599 dissertation Daemonologie. The reality is clear and disturbing: some of the victims of incubi were no doubt the victims of sexual assault or rape by real-life men who blamed non-existent spirits. As some of those women inevitably became pregnant, even more bizarre spiritual explanations had to be fabricated to avoid the rapists from being implicated.

If any of that reminds you of Rosemary’s Baby, there’s good reason.

Some of the Merlin legends hold that he was the child of a princess and an incubus. This is an illustration from The Birth of Merlin, or, The Child Hath Found his Father, a 1622 play by William Rowley.

The death of the ghost

As an adult, I’ve never believed in ghosts, and sleep paralysis provides the scientific explanation for the vast majority of people’s ghostly experiences, as well as encounters with extraterrestrials. If someone’s story of a ghostly encounter begins with ‘I was in bed’ or ‘I was asleep’ or ‘I’d nodded off on the sofa’, then an eerie description of a hallucination is sure to follow.

Sorry if you find that boring and unromantic. I disagree, though. I find the strange creations of our minds completely amazing, and what I love most is the way every person’s experiences are completely unique to them, yet tie them into an archetype of human experience.

It’s baffling for me to read that only 8% of people will experience sleep paralysis in their lives. That’s the Sleep Foundation’s statistic; Wikipedia gives a very wide margin for error of “between 8% and 50%”. I’ve no idea of the reality, but it seems unlikely to me that so many cultures would have such rich folklore about sleep paralysis if it affected fewer than one in every ten people.

An illustration by Kasia Walentynowicz

How can I remove this demon from my chest?

While I quite enjoy hallucinations, though, others obviously don’t ever want them again, and I could do without sleep paralysis. So what can be done? I rarely have episodes any more, and this is what has worked for me:

It’s not actually true that you’re completely paralysed: I’ve found that I can wiggle my toes and scrunch up my face. It doesn’t seem to wake me up, but in the midst of an episode, it’s slightly reassuring that I have control over some parts of my body. I think it also seems to hasten me falling back to sleep. This fits in with Latvian folklore, which states that people under attack by Lietuvēns (which is attempting to torture or strangle them) must move the toes of the left foot to escape.

Remember that you aren’t suffocating - you’re just breathing passively. Once you know that, it stops you panicking so much.

Cut out caffeine. The caffeine in some coffees has a half-life of up to six hours, so if you don’t want the effects to impinge on your sleep quality, you can probably get away with a cup in the morning if you then go caffeine-free afterwards. I allow myself one cup of caffeinated tea first thing, and then I try to stick to redbush thereafter. Even decaffeinated tea contains enough caffeine to affect our brains. If you’re one of those people who think caffeine doesn’t affect you (I used to be one of them), you’re wrong.

Quit the job that’s stressing you out. I’m being facetious, obviously, but I did do this, and it definitely helped a lot.

All that stuff about sleep hygiene (going to bed and getting up at the same time each day, keeping the bedroom sacrosanct, avoiding using your phone and laptop for a couple of hours before bed) really does help.

I don’t sleep on my back.

Baths. I’ve not seen this anywhere, but they’re bound to help.

From what I’ve read about other people’s experiences, trauma seems to instigate episodes of sleep paralysis, and they’re terrifying, especially for children. People report growing out of it, but where it’s available and affordable, long-term psychotherapy definitely helps, as it does with all manner of stresses and anxieties that exacerbate sleep paralysis.

For actual scientific information and advice on sleep paralysis, head to the NHS page on sleep paralysis or to the Sleep Foundation.

May you sleep soundly and without visitations from hags, mares, lustful demons or other supernatural intruders. And remember: wiggle your toes.

Newsletter

The second of my monthly newsletters will be making its way to inboxes in a few days. If you’d like your inbox to be amongst them, you can sign up here.